From A* to MARL (Part 3 - Planning Under Uncertainty)

An intuitive high-level overview of the connection between AI planning theory to current Reinforcement Learning research for multi-agent systems. This part focus on MDP and planning under uncertainty.

- A* to MARL Series Introduction

- Single-Agent Planning Under Uncertainty

- Generalizing to Multi-Agent MDPs

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgment

A* to MARL Series Introduction

Research of Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Multi-Agent RL (MARL) algorithms has advanced rapidly during the last decade. One might suggest it is due to the rise of deep learning and the use of its architectures for RL tasks. While it is true at some level, the foundations of RL, which can be thought of as a planning problem formulated as a learning system, lie in AI planning theory (which has been in development for over 50 years). However, the connection between RL and planning theory might seem vague, as the former is related to deep learning for most practitioners nowadays.

This series of articles aims to start from the classical path-finding problem, with strict assumptions about the world we are tackling (deterministic, centralized, single-agent, etc.) and gradually drop assumptions until we end up with the MARL problem. In the process, we will see several algorithms suited for different assumptions. Yet, an assumption we will always make is that the agents are cooperative. In other words, they act together to achieve a common goal.

It is important to note that this series will focus on the “multi-agent systems path” from A* to MARL. This will be done by formulating the problems we want to solve and the assumptions we make about the world we operate in. It certainly won’t be an in-depth review of all algorithms and their improvement on each topic.

Specifically, I will review optimal multi-agent pathfinding (Part 1), classical planning (Part 2), planning under uncertainty (Part 3), and planning with partial observability (Part 4). Then, I will conclude our journey at RL and its generalization to multi-agent systems (Part 5). I will pick representative algorithms and ideas and will refer the reader to an in-depth review when needed.

Single-Agent Planning Under Uncertainty

The previous chapter dealt with planning in a deterministic world, where a planner can generate a sequence of actions, knowing that if they are executed in the proper order, the goal will necessarily result. Now, we turn to the case of nondeterministic worlds, where we must address the question of what to do when things do not go as expected.

One might suggest naive solutions to that problem. For example, we can monitor (by some sensor) for “failures” and initiate replanning in that case. Yet, replanning at each failure would be undesirable for many real-world applications, as it would be too slow. On the other hand, we can plan a reaction for every possible situation that might occur during plan execution. It would generate a fast and robust plan, yet would be highly expensive to find that plan for non-trivial domains with many states. Therefore, we seek algorithms that deal with the uncertainty at planning and yield robust plans.

Some level of uncertainty exists in almost anything. How can we take it into account when planning?

MDP - Representing Uncertainty In Planning

In the previous post, we learned how to represent a planning problem with STRIPS/PDDL. We defined the domain with a set of actions and conditions. The specific problem is defined with an initial state and a goal state. Yet, it is not trivial how to extend this language to entail uncertainty.

The planning community adopted the Markov Decision Process (MDP) to model the problem. An MDP is defined by the following: state, actions, transition function, and reward function. The state and actions are straightforward and are essentially the same as in the classical planning problem. The transition function assigns a probability for each triplet of (s1,a,s2). It defines the probability for ending in state s2, after applying action a at state s1. The reward function simply assigns a reward with being in a state and performing an action.

A crucial assumption underlying the modeling of a planning problem as an MDP is the Markov property. Basically, it says that the future is independent of the past given the present. That is the reason we could define it only by the triple of (s1,a,s2), considering (s1,a) as the present, and s2 as a possible future. If we were not making this assumption, we would be in trouble trying to define the transition function, as we would need to associate each possible path with a probability. However, it is not trivial to determine if the Markov property indeed holds for a given problem. A toy example would from this MSE answer considers an urn with two red balls and one green ball. Two draws are made from the urn, without replacement. Knowing only the last drawn ball’s color does not contain the same information as knowing both draws. However, in this post, we will assume that the Markov property holds. I refer the curious reader to read Markov or Not Markov.

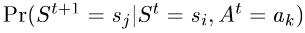

Formally, according to the Markov property, the transition function is defined as:

The transition function. It models the probability of reaching state Sj when action Ak is applied in state Si.

Optimality

Given the problem formulation as MDP by the state, actions, reward function, and a transition function, we need to define what is the optimal solution to that MDP? The classical planning problem was a sequence of actions from the initial state to the goal state. However, a single sequence of actions is not suitable for indeterministic problems. Therefore, we seek a policy that maps from states to actions. The optimal policy is the policy that maximizes the expected rewards. In other words, following the optimal policy from every state would yield, on average, the highest reward among all possible policies. Do you see the implicit assumption we are making when defining the optimal policy that way? In a way, we assumed a rational agent.

Some of you might wonder how an MDP is a generalization of the planning problem? Well, typical classical planning problems can be viewed as MDPs in which the world is deterministic and there is only a single goal (e.g., the reward is 0 for all states except the goal state which is 1).

Before proceeding to the algorithms that aim to find an optimal policy for the MDP, note that the uncertainty we deal with right now stems only from control errors and not from sensor errors. We assume that we fully observe the state and have certainty in that observation.

Finding the Optimal Policy - Solving MDPs

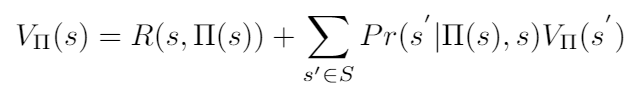

Algorithms that solve an MDP aim to find the optimal policy. We defined it as the policy that yields, on average, the highest reward from every state. Mathematically, we wish to find the policy that maximizes a value function overall states. The value function at state s for a policy (denoted by π) is:

The value function of policy π, evaluated at state s.

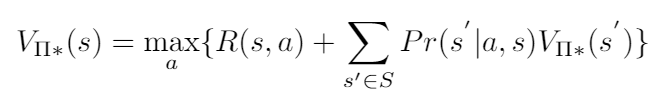

Finding the optimal policy boils down to solving the following optimization problem:

The optimal policy is the policy that chooses the action that maximizes the value function for every state.

If reading those formulas feels intimidating or unintuitive, just think a moment about what they basically mean. They suggest that to figure out what action to take in each state to achieve the optimal policy, we just need to average over all possible states, follow the policy from that state, collect the rewards, and weigh each of them by its probability of occurring. Run it over your head, and it will suddenly seem like a pretty naive brute-force solution.

The most commonly-known algorithms for this optimization problem, named value iteration and policy iteration, use Dynamic Programming. The main idea is to solve the problem by breaking it down into simpler sub-problems recursively.

Notes on MDP

- Usually, a variant of this formula that extends it to consider discounted rewards is being used. Discounted rewards basically mean that a reward earned sooner is worth more than one earned later, which is the case at many real-world problems.

- MDPs can be split into two families - finite and infinite horizon MDPs. Put simply, finite-horizon MDPs deal with problems with finite execution time span, where infinite horizon MDPs deal with problems that “run forever”. I focus on finite MDPs in this post.

Value Iteration & Policy Iteration

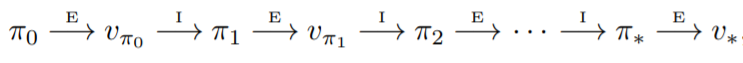

The policy iteration algorithm alternates between two stages - policy evaluation and policy improvement. At the evaluation stage, we treat the current policy as fixed and compute the value function for each state. At the improvement stage, we modify the policy to choose the best action for each state according to the value function we evaluated at the last stage. We perform a couple of evaluation and improvement steps until no change is made to the policy. In other words, the improvement step does not change the action to take in every state. The sequence of stages performed will be as:

A sequence of evaluation & improvement stages performed by policy iteration algorithm.

The value iteration algorithm suggests combining those two stages into one stage. Starting with an initial value function set to zero (i.e., all states have the value 0), it updates the value function by iterating over all possible actions for each state and choosing the action that maximizes the current rewards plus the next-state value function. It does so until no change to the value function is made for all states. Then, using the optimal value function, it constructs the optimal policy by choosing the action that maximizes the value function for each state.

As both of those algorithms are widely known, I am not diving into the algorithm implementation details. I refer you to look at some nice and simple implementations of policy iteration and value iteration algorithms. Moreover, despite these algorithms tend to converge in relatively few iterations, each iteration requires computation time at least linear in the size of the state space. This is generally impractical since state spaces grow exponentially with the number of problem features of interest. This problem is sometimes denoted as the “curse of dimensionality”.

Generalizing to Multi-Agent MDPs

Generalizing the MDP we described to the multi-agent case requires us to remember a crucial assumption we made along the way about the nature of the agents. We assumed that they are cooperative in the sense that they act together to achieve a common goal. The research about noncooperative agents is an exciting research area that lies in between game theory and AI. It focuses on the case where two (or more) agents with different interests, formalized through their reward function, co-exist in the same world and their actions can affect each other’s rewards. This is off-topic for now, but I hope to write about it another time.

Coming back to our multi-agent MDP (MMDP) with cooperative agents that operate to maximize a joint reward function, one might wonder why can’t we just model it as a “big MDP”, where the action space is the joint action space of all agents, and the state space is the joint state space of all agents. It is of course doable but makes a crucial assumption that is inappropriate for many multi-agent systems. It assumes the existence of a central entity that derives the plan for all agents and sends them their individual optimal policies. Therefore, researchers have focused on the decentralized case, where each agent should derive his own optimal policy. In this case, the main challenge is how to combine multiple individual optimal policies to an optimal joint policy.

Mutli-Agent MDP (MMDP)

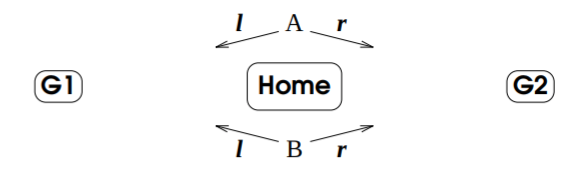

MMDP specifies a decentralized MDP for a multi-agent system, where each agent knows the complete problem MDP (All states, for all actions, and the corresponding transition function between states given actions for all agents). Therefore, each agent can find the optimal policy by solving the complete MDP on his own. From those optimal policies, one can compose the joint policy. The joint policy is a mapping between each state to every agents’ action. Yet, is building a joint policy from several optimal policies derived individually ensures optimality? Unfortunately, no. Since the optimal policy is not unique, how can we be sure that all agents follow the same optimal policy? A simple yet famous example that illustrates the need for coordination due to multiple optimal policies derived in a decentralized manner is shown below. Both agents (named A and B) solve the joint MDP. The reward is 1 when both agents move to the same location (G1 or G2) and 0 when they move to different locations. There are two optimal policies for that MDP, the first when both agents choose to go to G1 and the second when both choose to go to G2. Yet, what happens if agent A chooses the first optimal policy, and agent B chooses the second?

Coordination Problem

A two-agent coordination problem.

This problem is generally referred to as the coordination problem. There are mainly three approaches to solve it. First, one may assume the agents’ ability to communicate (“Let’s turn left!”). Second, shared conventions might be defined that would result in a consistent pick of an optimal policy for all agents (“Choose actions lexicographically. If both left and right are optional, choose left!”). Third, if not shared convention or communication is given, the agents can learn to coordinate if several games can be played (“Ah-ah. I see you choose to go left in this situation. See you next time!”). We will not dive into the different algorithms that solve the coordination problem. I encourage you to follow the links above for further information.

However, even if we assume the coordination problem to be solved, letting every agent solve the complete MDP comes with a high computational cost. As we already saw in MAPF and multi-agent planning, a linear increase in the number of agents induces an exponential increase in the computational complexity, if the multi-agent problem is treated naively. In general, solving the complete MDP for each agent would be intractable for systems with more than a few agents. Moreover, the assumption that all agents know about all other agents, states, and actions does not hold in many real-world systems.

Decentralized MDP (DEC-MDP)

Therefore, the model of DEC-MDP (Decentralized MDP) is suggested. In contrast to MMDP, it does not assume that each agent knows the full MDP. It only assumes that the joint MDP state can be derived from the set of states of all agents. But how can we solve a DEC-MDP optimally? Unfortunately, it has been shown that decentralized multi-agent MDPs are very hard to solve optimally (NEXP-Complete). However, several attempts to model the decentralized MDP in a tractable way for specific cases have been suggested.

Specific Cases of DEC-MDP

For example, Transition-Independent MDP (TI-MDP) is a specific case of a DEC-MDP where the state transitions of an agent are independent of the states and actions of the other agents. In essence, it is the case when the actions taken by an agent do not affect other agents. Note that it does not mean that we can just decompose the n-agent DEC-MDP into n different MDPs. We could decompose it only if we further assume reward independence, which basically means that the reward function can be expressed as a sum of n-different reward functions, where each reward function knows only about a single agent’s actions. A motivating example is a group of robots that scan a field together to find something. The reward for scanning a given piece of land is lower if another agent already scanned it before, therefore the reward is not independent. An optimal algorithm for TI-MDPs is detailed in their paper.

While IT-MDP and other sub-classes of DEC-MDP yield optimal policies, this is not the case with the general DEC-MDP. Therefore, many research efforts focused on finding approximate solutions.

Approximate Solutions for DEC-MDP

Finding approximate solutions to DEC-MDP can be divided into two approaches. The first approach suggests algorithms with a guarantee on the solution quality, by measuring how worse their solution is from the optimal solution. One such algorithm that converges to an ε-optimal solution was suggested in 2005 by Bernstein in his Ph.D. thesis. The second approach suggests algorithms with no performance guarantee. We will see algorithms from this approach in our next chapter when we will go over algorithms for DEC-POMDPs.

Conclusion

An important milestone towards MARL is the notion of uncertainty which was introduced in this post. First, we defined how to reason about uncertainty for planning problems using MDP, and what is the notion of optimality under uncertainty. Then, we learned about algorithms that aim to find those optimal policies. Finally, we saw several frameworks that generalize the MDP into multi-agent settings. Those frameworks differ by several assumptions, such as the existence of a central authority and the interdependency between the agents. In general, an optimal solution to the decentralized multi-agent MDP is highly hard to find, and we briefly discussed approaches to finding approximate solutions.

Next, we will drop another crucial assumption about observability and introduce the framework of Partially Observable MDPs (POMDP). Similar to what we did in this chapter, we will see the generalization of this POMDP framework to the decentralized multi-agent case. Then, we will be ready to finish our journey at MARL.

Acknowledgment

I want to thank Roni Stern, my MSc thesis supervisor. My interest in this area and large parts of this blog series stems from the wonderful course he teaches on multi-agent systems at Ben-Gurion University, which I had the privilege to take.