From A* to MARL (Part 2 - AI Planning)

An intuitive high-level overview of the connection between AI planning theory to current Reinforcement Learning research for multi-agent systems. This part focus on AI Planning.

- A* to MARL Series Introduction

- Single Agent AI Planning

- Generalizing to Multi-Agent Planning (MAP)

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgment

A* to MARL Series Introduction

Research of Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Multi-Agent RL (MARL) algorithms has advanced rapidly during the last decade. One might suggest it is due to the rise of deep learning and the use of its architectures for RL tasks. While it is true at some level, the foundations of RL, which can be thought of as a planning problem formulated as a learning system, lie in AI planning theory (which has been in development for over 50 years). However, the connection between RL and planning theory might seem vague, as the former is related to deep learning for most practitioners nowadays.

This series of articles aims to start from the classical path-finding problem, with strict assumptions about the world we are tackling (deterministic, centralized, single-agent, etc.) and gradually drop assumptions until we end up with the MARL problem. In the process, we will see several algorithms suited for different assumptions. Yet, an assumption we will always make is that the agents are cooperative. In other words, they act together to achieve a common goal.

It is important to note that this series will focus on the “multi-agent systems path” from A* to MARL. This will be done by formulating the problems we want to solve and the assumptions we make about the world we operate in. It certainly won’t be an in-depth review of all algorithms and their improvement on each topic.

Specifically, I will review optimal multi-agent pathfinding (Part 1), classical planning (Part 2), planning under uncertainty (Part 3), and planning with partial observability (Part 4). Then, I will conclude our journey at RL and its generalization to multi-agent systems (Part 5). I will pick representative algorithms and ideas and will refer the reader to an in-depth review when needed.

Single Agent AI Planning

In Part 1, we dealt with the pathfinding problem, where our goal was to find the shortest path from start to goal for a set of agents. In this article we’ll discuss AI Planning, which can be thought of as a generalization of the MAPF problem. In general, planning is the task of finding a sequence of actions that will transform the start state into the goal state. We will start with the single-agent planning problem, and generalize to multi-agent, analogous to our path from the previous post.

Brief History of AI Planning

From its early days, the holy grail of AI planning was creating a domain-independent problem solver. This domain-independent problem solver would hopefully be able to tackle all kinds of planning problems, ranging from playing games to making cookies. In 1959, the GPS paper introduced a general problem solver which could solve problems expressed by a well-formed formula. It was designed for theorem proving. Yet, for several reasons, it was not well-suited for planning problems. For example, it was not intuitive how to express concurrent events, and preferences for generated plans.

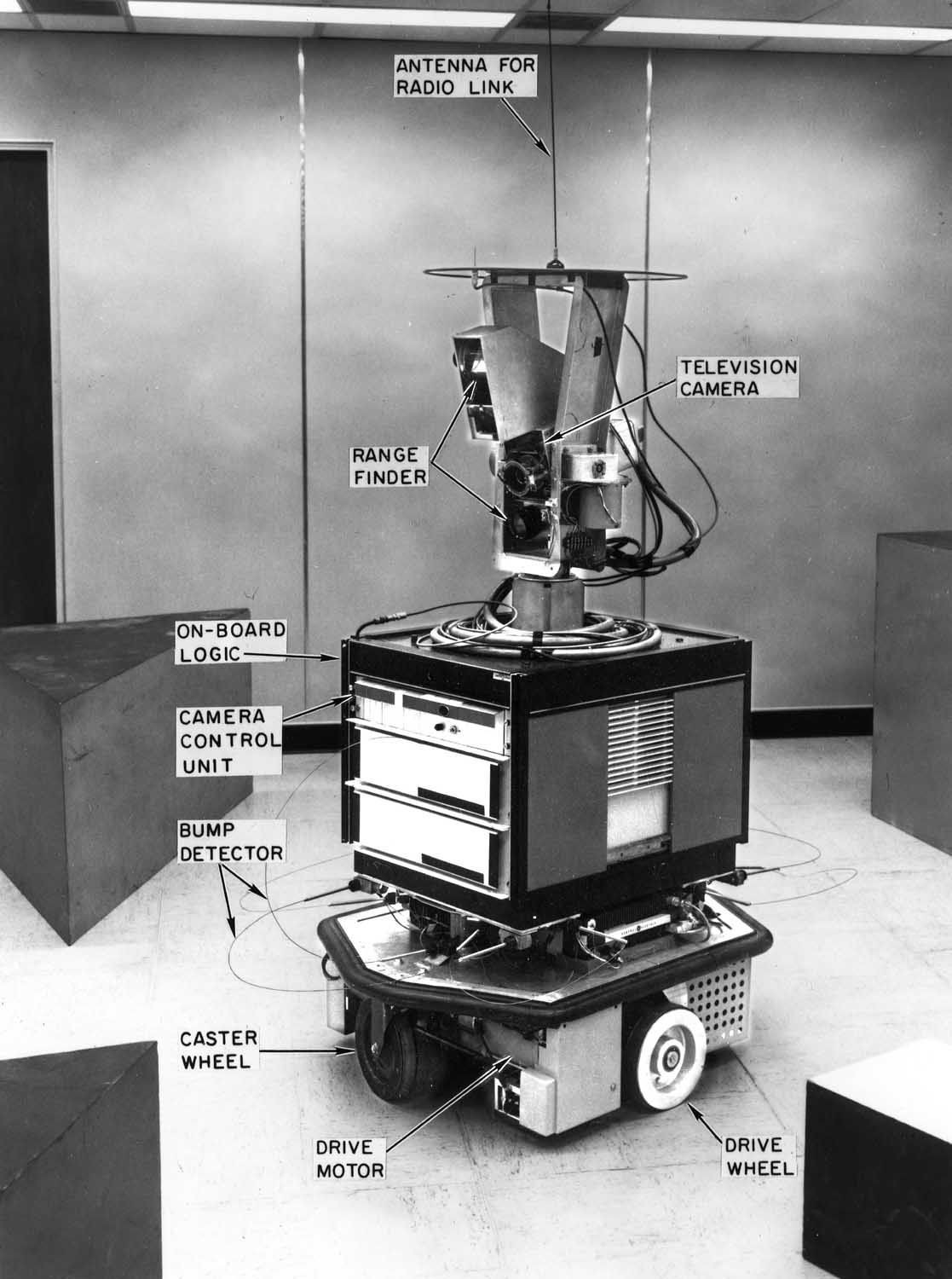

This work motivated researchers from Stanford Research Institute, who have worked on Shakey the robot, to develop a well-formed language and domain-independent planning algorithm that is suited to planning, called STRIPS. Several other languages and planners were suggested over the years. The development of several different languages, with different expressive power, made the comparison between the planners a difficult task. An attempt to standardize AI planning was done in 1998, called PDDL.

Shakey the robot, a high-impact research project from the 60s. Oh, and why “Shakey”, you ask? Well, “it shakes like hell and moves around”.

Classic AI Planning Assumptions

In the classic planning problem, we deal with deterministic environments that can be fully observed. For now, we also assume that there is only one agent.

Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL)

PDDL is a language we use to define the initial state, goal state, and actions our agent can perform. In essence, a PDDL problem is defined by conditions, actions, initial state, and goal state. A set of conditions describes a state, and actions defined by the effects they cause and preconditions under which they are applicable.

A famous planning example is the air cargo load problem. We will focus on a simple problem, with 2 cities (TLV and NYC), two airplanes (called P1, P2), and two different cargo (C1, C2) we want to transfer between the cities. At our initial state, we have C1 and P1 at TLV and C2 and P2 at NYC. Our goal is to have C1 at NYC and C2 at TLV. Let’s write it in PDDL.

Init(At(C1, TLV) ∧ At(C2, NYC) ∧ At(P1, TLV) ∧ At(P2, NYC))

Goal(At(C1, JFK) ∧ At(C2, SFO))

Now it’s time to define the actions. Basically, we want our airplanes to be able to load cargo, fly between cities and then unload the cargo. Pretty straightforward. It can be defined as simply as:

action(LOAD(cargo,plane,city),

precondition: At(cargo,city) ∧ At(plane,city)

effect: ¬At(cargo,city) ∧ In(cargo,plane))

action(FLY(plane,from,to),

precondition: At(plane,from)

effect: ¬At(plane,from) ∧ At(plane,to))

Note that, even though it may be unintuitive, once an airplane loaded cargo, the cargo is no longer defined to be at the city, as defined by the effect of the “LOAD” action. Also, you probably noticed that the “UNLOAD” action is missing. Can you come up with it yourself?

Important note - To fully define the problem in PDDL, we need to properly define some other things which I intentionally skipped. For example, we need to define the types we are using (Cargo, Airplane, etc.). You will encounter that in real PDDL problem definitions, yet I believe it is not required for understanding the essence of formulating a classic AI problem. If you are interested in the full definition, I wrote it on STRIPS-fiddle. You can solve it and find the 6-steps solution!

AI Planning Algorithms

Now that we know how to define our planning problem, it is time to learn how to solve it. The naive approach for solving the planning problem would be to first apply all applicable actions to the initial state to create a set of successor states. Then, we would continue to apply all applicable actions to these successors until we reach a goal state. However, since the number of applicable actions might be quite large, this naive approach is impractical. Does it remind you of uninformed graph search algorithms, such as BFS/DFS? Yep, that’s exactly that. So one might ask to follow an A* informed approach and use a heuristic. Indeed, from classical pathfinding, we know that adding a good admissible heuristic is essential for effectively solving large state-space problems. Also, we remember that for A* to ensure optimality, the heuristic must be admissible (i.e., never over-estimate the cost of reaching the goal).

Heuristics for Domain-Independent Planners

Yet, a problem arises. How can we come up with a heuristic, which should encode problem-specific knowledge, in a problem-independent way? We need a method that automatically generates an admissible heuristic function from a STRIPS problem definition. A simple approach would be to relax our planning problem P into a simpler problem P`, compute the optimal cost for P`, and use it as a heuristic. A possible relaxation of P is removing all actions “negative effects” (i.e., all effects that make a condition false). For example, in P`, even after loading cargo to an airplane, it stays in the airport. Although this method would indeed produce an admissible heuristic, computing it might still be NP-Hard, which misses the goal of the heuristic, which is to inform the search efficiently towards the goal.

In 1998, the HSP algorithm proposed a method to approximate the heuristic. Essentially, it proposes to decouple the goal conditions and compute the number of actions from a given state to satisfy each condition separately. Then, the heuristic value would be the sum of all actions to achieve all conditions.

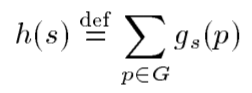

Value of heuristic in the state s is the sum of actions to achieve each condition, p, of the goal G.

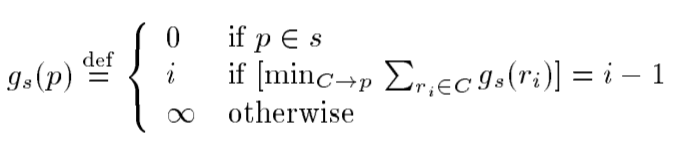

To compute the number of actions to satisfy each condition, we iteratively updating the following function until no changes is observed in its values:

The number of actions to achieve a condition, p, is updated iteratively until the function does not change.

At each iteration, we apply all actions whose corresponding preconditions hold in the current state (s).

Assuming that the goal conditions are independent and solving the relaxed P` problem result gives us an informative heuristic, which as shown in various AI planning competitions, is useful to solve large problems. Yet, those assumptions come with a price. This heuristic is not admissible, since independent goal conditions might contain redundant actions.

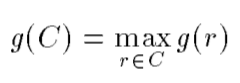

However, we can create a less informative but admissible heuristic if we choose to swap the number of solved problems for optimality. We can take a variation of the heuristic above, which is called “max-heuristic”. Basically, instead of summing over all independent goal conditions, we take the condition with the highest number of actions to satisfy.

An admissible heuristic is given by counting the largest number of actions to achieve one of the independent conditions of the goal.

Go Backwards!

Whether we are using the admissible or inadmissible heuristic, we still need to compute it for every state to use it in a heuristic search algorithm, such as A*. Computing this heuristic for every state consumes ~80% of the search time. A simple yet effective solution is to reverse the search direction. Searching backward, from goal state to start state, is called regression search.

Intuitively, the regression approach is the process of: “I want to eat, so I need to cook dinner, so I need to have food, so I need to buy food, so I need to go to the store”. At each step, it chooses an action that might help satisfy one of the goal conditions.

The crucial point of using the regression approach is that the initial state does not change during the search, therefore we can utilize the already computed heuristic, and perform the search more efficiently. There are subtle points I am skipping regarding the implementation of using the regression approach with HSP (denoted as HSP-r). More details can be found in the HSP-r paper.

Beyond Search Algorithms

As we previously learned, in the case of MAPF problems, algorithms developed for one problem might be useful to solve another problem. It is also true in AI Planning, where a powerful planner is given by converting the planning problem to a Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT). One such planner is called SatPlan.

Quick Recap

Before continuing to multi-agent systems, let’s do a quick recap. We saw a language to represent planning problems and their corresponding domain, called STRIPS or PDDL. Then, we saw several approaches to construct a domain-independent solver for those planning problems. Some of them were naive uninformed search algorithms, and others are a bit more complicated. Of course, it is only a fraction of the algorithms that exist that tries to solve AI planning problems. Check out this chapter on AI Planning for more details.

Generalizing to Multi-Agent Planning (MAP)

At our logistics toy example, there were 2 airplanes. We can easily imagine real-world logistics problems with hundreds of airplanes or more. As we previously learned in the context of MAPF, a naive generalization to multi-agent systems results in an exponentially harder problem relative to the number of agents. It is much the same with MAP. Therefore, We need to find an efficient way to exploit a common fact for real-life multi-agent systems - the different agents might be loosely coupled. This recurring theme of decoupling planning problems to sub-problems and merge their solutions is a fundamental idea that is at the heart of most multi-agent systems. Indeed, we have seen it at MAPF and we will see it in the next post about MMDP as well.

Furthermore, real-life multi-agent planning might involve several different parties that collaborate to achieve a common goal, but desire to keep some information (i.e., actions and conditions) private. Consider a military covert mission where multiple robots coordinate behind enemy lines. We would not want each robot to contain the full information about all other robots (such as the number of robots, their location, equipment, etc.), since it might be compromised. We can also think of several enterprises that cooperate for a specific mission, and do not want to reveal private information.

Currently, as far as I know, in the multi-agent planning community, the work on privacy-preserving algorithms for multi-agent planning is an active research area. Although it is motivated by privacy-preserving, it is useful for distributed multi-agent planning, which provides efficient algorithms for loosely coupled multi-agent planning problems. It is an interesting line of work, but we will skip it and continue our path to MARL. I refer the curious reader to read about MA-STRIPS, MAFS, and Secure-MAFS.

Conclusion

We started from the definition of a domain-independent planning problem. After a quick historical overview and a STRIPS toy problem, we learned about the search-based algorithms, how heuristics can be automatically extracted from the planning problem, and the importance of the search direction. Then, we saw algorithms that are not search-based that solve the planning problem. We examined the case for the generalized MA-STRIPS problem and saw its applications to distributed planners and privacy-preserving conditions.

Next, we will continue our path to MARL, as we will drop the assumption about the deterministic actions and full knowledge of the state. In particular, We will discuss the Markov Decision Process (MDP) and Partial-Observable MDP (POMDP), which as we will see later, are the foundations of model-based RL.

Acknowledgment

I want to thank Roni Stern, my MSc thesis supervisor. My interest in this area and large parts of this blog series stems from the wonderful course he teaches on multi-agent systems at Ben-Gurion University, which I had the privilege to take.